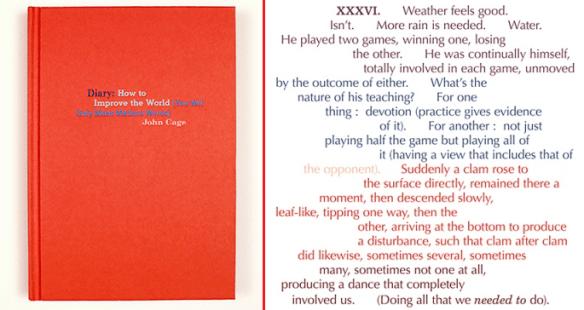

This post is part of a series on John Cage’s “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).” For earlier installments of the series, please visit: Introduction, Part I, & Part II

Imagine yourself listening to the radio.

Nothing too out of the ordinary, just you by yourself in a room, the radio dial tuned to your favorite station. Maybe you’re grooving to some jazz tunes, gettin’ down to James Brown, rocking out to the Top 40, or maybe even tuning in to talk radio (you know, if you’re into that).

Now imagine yourself listening to 12 radios. All at once—and all tuned to different channels.

Yes, that’s right. Now you are simultaneously listening to jazz and James Brown, Top 40 and weather forecasts, talk radio and even (Heaven help us) the country channel.

That was precisely the premise behind John Cage’s 1951 piece “Imaginary Landscape No. 4,” scored for 24 performers at 12 radios. It is organized chaos. Of course, the piece doesn’t describe a physical landscape but rather, a landscape of the future—a landscape exploring the possibilities of what were, at the time, new and unknown technologies.

“It’s as though you used technology to take you off the ground and go like Alice through the looking glass,” Cage said of his inspiration for the piece.

Reading through Cage’s “Diary” is a bit like falling through the looking glass, as well. His reflections can be silly and nonsensical, curious and contrary, fragmented and, at times, even frightening. There is no topic left untouched: art, music, philosophy, culture, culinary arts, and even politics.

In fact, it’s a bit like listening to 12 radios at once. It’s a random mix of the everyday along with the breaking news; a thousand stories told all at once. One moment, he’s discussing political summit meetings and the next, he’s comparing the musical philosophies of Stravinsky and Schoenberg. (Cage was, in fact, a student of the latter.)

But it is not until Part III of his eight-part diary that he actually digs into the more social and political aspects of the work—the actual “How to Improve the World” part, so to speak—and he does this in a myriad of ways.

Some remarks are just petty observations about everyday inconveniences:

“Something needs to be done about the postal services,” he says dryly. “Either that or we should stop assuming just because we mailed something it will get where we sent it.”

While others have much more serious implications:

“Bertrand Russell asks American citizens: Can you justify your government’s use in Vietnam of poison chemicals and gas, the saturation bombing of the entire country with jelly-gasoline and phosphorus?” he asks gravely. “Napalm and phosphorus burn until the victim is reduced to a bubbling mass.”

Truth be told, I was caught a bit off guard by his abrupt (and clearly weighted) mention of the war in Vietnam—I had to remind myself that as otherworldly as some of Cage’s music may be, he did not, in fact, exist in a vacuum. He was an idealist, yes, but he was also a socially- and politically-conscious artist—he was a thinker and a citizen of the world, and his art was constantly being shaped and influenced by his surroundings.

“In music it was hopeless to think in terms of the old structure (tonality), to do things following old methods (counterpoint, harmony), to use the old materials (orchestral instruments),” he says. “We started from scratch: sound, silence, time, activity.”

“In music it was hopeless to think in terms of the old structure (tonality), to do things following old methods (counterpoint, harmony), to use the old materials (orchestral instruments),” he says. “We started from scratch: sound, silence, time, activity.”

In other words, he started from what was around him. He created music scored for 12 radios because he was growing up during the rise of radio and broadcasting, the rise of music being transmitted electronically rather than performed live, in-person.

In fact, “Imaginary Landscape No. 4” was a reaction against radio, more than anything. Cage didn’t like the radio, so he began using it in a new way—as a musical instrument itself, rather than as a transmitter of music. He wrote a number of pieces featuring radio, and by the 1980s it was one of his favorite instruments:

“Almost as favored by me as the sounds of traffic,” he said in a 1986 interview with artist Richard Kostelanetz.

For Cage, sound is music, regardless of the context or the intention.

“I love sounds, just as they are, and I have no need for them to be anything more than what they are,” he says. “I don’t want them to be psychological. I don’t want a sound to pretend that it’s a bucket, or that it’s a president, or that it’s in love with another sound. I just want it to be a sound.”

Indeterminacy was a way of creating sound without meaning—crafting unpredictable and arbitrary music that could exist only in that moment. No narrative, no love story, no tragedy, no flowing melodies, and no meaning—just the simple experience of sound.

“Sounds everywhere,” he says in his diary. “Our concerts celebrate the fact concerts’re no longer necessary.”

Our world is saturated with music and art—it exists everywhere around us if we bother to look at and listen to it. Cage’s work reminds us to stop recreating the classics of the past and to start opening ourselves up to the music of the present.

“We have everything we used to have,” he says in his typical deadpan manner. “The Mona Lisa’s still with us for instance. On top of which we have the Mona Lisa with a mustache. We have, so to speak, more than we need.”

I’m pretty sure I can hear him smiling as he says it, but he doesn’t betray even a hint of laughter. He’s right—we do have more than we need. We have plenty of masterpieces from throughout the centuries, but if we simply continue regurgitating the same ideas over and over, then we are just making a mockery of the originals.

Perhaps the real art is in shifting our understanding of art itself, abandoning our expectations, and opening our minds, hearts, eyes, and ears to the present. Perhaps the real art is in listening to 12 radios at once and hearing the beauty of the sounds themselves—no meaning, just music.

“Art instead of being an object made by one person is a process set in motion by a group of people,” he says. “Art’s socialized. It isn’t someone saying something, but people doing things, giving everyone (including those involved) the opportunity to have experiences they would not otherwise have had.”

Go to the next installment: Diary: How to Read John Cage – Part IV