This post is part of a series on John Cage’s “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).” For earlier installments of the series, please visit: Introduction, Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V.

Since its invention in the early 18th century, the piano has been the cornerstone of the Western classical music tradition. It has been the conduit for the musical masterpieces of Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and countless other composers. It has been the staple instrument in all studies of Western music theory, the standard instrument for accompanying soloists, and the shimmering star of recital stages around the globe.

The depth and breadth of classical piano repertoire is astounding. As an instrument, it has garnered a reputation as one of the most beautiful and most perfect modes of human expression—and John Cage threw a wrench in it. Literally.

In 1940 Cage invented the prepared piano: a grand piano that has had its sound altered by placing everyday objects such as screws, bolts, and pieces of rubber on or between the strings.

His creation shocked and intrigued audiences around the world. To place everyday objects inside a grand piano seemed almost sacrilegious—or at the very least, iconoclastic.

But what he created was a new type of beauty. What he created was an entire percussion orchestra from just a single instrument.

“There are two kinds of music that interest me now,” Cage says in Part VI of his “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).” “One is music I can perform alone. Other’s music that everyone (audience too) performs together.”

And while the notion of a prepared piano may seem unconventional, eccentric, or even extravagant to the Cage critics among us, he actually created this musical contraption in response to a very genuine need: while working as a composer and accompanist at Seattle’s own Cornish College of the Arts, he was commissioned to write music for a dance by Syvilla Fort. Presented with the challenge of writing dance music for a small stage with no room for a percussion group, he simply—well, improvised.

Cage wrote extensively for percussion because, as he himself admitted: “I certainly had no feeling for harmony.” And in a way, I guess he didn’t have much feeling for melody either.

“When I was in the sixth grade, I signed up for the Glee Club,” he says drearily into my left headphone. “They said they’d test my voice. After doing that, they told me I didn’t have one.” His voice meanders over into my right headphone: “Now there’re more and more of us, we find one another more’n’more interesting. We’re amazed, when there’re so many of us, that each one of us is unique, different from all the others.”

Perhaps Cage wasn’t a very good musician in the traditional sense—but that’s precisely what enabled him to explore music in new and nontraditional ways. It’s what allowed him to push the boundaries and open new doors to what music could be and how everyone, not just the classically-trained professionals, could be a part of it.

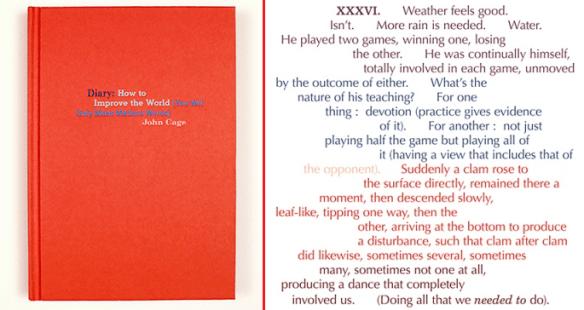

“To raise language’s temperature we not only remove syntax,” he says slowly, “We give each letter undivided attention, setting it in unique face and size; to read becomes the verb to sing.”

Maybe that’s what inspired the colorful collage of different typefaces that constitute the entire diary. The language takes on a physical as well as an aural presence—conveying the music of the words through the visual variances between them.

Maybe that’s what inspired the colorful collage of different typefaces that constitute the entire diary. The language takes on a physical as well as an aural presence—conveying the music of the words through the visual variances between them.

“Ancient Chinese was free of syntax,” Cage says blandly. “Words floated in no-mind space. With the passing of centuries, fixed relations between words became increasingly established. The history of Chinese language resembles that of a human body that, aging, becomes arthritic.”

When you stop and think about it, music and syntax are really quite similar: both are about arranging sounds to create pleasant, balanced, or meaningful statements. But these guidelines and rules limit us; they hinder our creativity, make us stiff and boring. After all, it was the infinite possibilities of the unpleasant, the imbalanced, and the unintentional that most inspired Cage.

“As we were walking along, she smiled and said, ‘You’re never bored, are you,’” Cage recalls softly. “(Boredom dropped when we dropped our interest in climaxes. Traffic’s never twice the same. We stay awake and listen or we go to sleep and dream.)”

At times, it’s difficult to tell when Cage is awake and when he’s dreaming. Throughout his diary he’ll shift quite abruptly from a serious discussion of technoanarchism to a whimsical analysis of racial politics, then drop off the edge of reality altogether with a humorous story or a surrealist musing.

“When can we get together?” Cage asks plainly. “‘It’s hard to say: I’m going out of town tomorrow and I’ll be back sometime today.’”

The notion of time as a social construct is yet another interesting notion throughout Cage’s music and philosophical meanderings.

Last summer I studied music composition at the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique in Paris, and on my first day our guide took us on a tour of the entire institute. The most fascinating room was the anechoic chamber: a room designed to absorb all reflections of sound, allowing for complete and total silence. They’d only let us stay inside a few minutes at a time, since the silence gets to people.

“John Cage used to spend hours in here,” the guide told me in a charming French accent. “But that’s not really legal.”

I left Paris enlightened.

“The outside walls of buildings in Paris are used for transmitting ideas,” Cage says. “Rue de Vaugirard, I read: La culture est l’inversion de l’humanité.”

Go to the next installment: Diary: How to Read John Cage – Part VII