by Peter Tracy

In the spring of 2017, I found myself sitting in Meany Hall, watching characters wander back and forth singing odd melodies accompanied by enormous, sculpture-like instruments arrayed across the stage. The instruments buzzed, rattled, and rang in ways I’d never heard before, but which immediately drew me in: I wasn’t sure just what I was watching, let alone what I was listening to—but I liked it.

This was the Seattle production of Harry Partch’s monumental music drama Oedipus, and it was an eye-opening experience. Later, I learned from a friend who played in the Partch ensemble that it was open to just about anybody: all you had to do was ask. Soon after, I did, and that decision has shaped my life as a musician ever since.

That Harry Partch’s one-of-a-kind instruments have been living in Seattle for the past five years is incredible, and it is one of the many things that currently make our city artistically unique. The instruments and the ensemble members who love them dearly are intimately connected to the local music community, and a new community of its own has even grown around the instruments during their stay here. For all of us in Seattle who have had the chance to interact with, listen to, and enjoy the instruments, however, there is a catch: the instruments may not be here for much longer.

The music of Harry Partch is difficult to describe, and in a sense it’s impossible to separate from the instruments it was written for and the man who wrote it. Partch was a mid-20th century American composer who wanted to get away from Western classical music’s standard tuning system, which divides the octave into the twelve equally spaced pitches we see repeated on the keys of the piano. He felt this system, which is referred to as equal temperament, limited harmony unnecessarily, and that music would be better served if it allowed for notes that fell somewhere in between the black and white keys. Music that uses these kind of “in between” notes and tiny intervals is often referred to as microtonal, and it can be jarring for those of us who are used to the Western classical tuning system. But for Partch, getting rid of equal temperament opened up a whole new world of harmony and sound that he thought was well worth pursuing.

To make this possible, Partch built an entirely new set of instruments, from enormous marimbas to microtonal lap guitars and percussion instruments made from airplane nose cones, cut Pyrex containers, and even artillery shell casings. All of these instruments utilize and fit into his own tuning system (a form of just intonation), and he composed pieces more or less exclusively for these instruments throughout his life.

But to reduce Partch’s work to an experiment in just intonation is really to miss the point: his instruments are works of visual art in their own right which allow for a combination of music, dance, and theatre that is whimsical, energetic, and one-of-a-kind. It’s the imagination and passion which resulted in the creation of these instruments that is really at the heart of Partch’s world.

“If you consider it in parts you sort of lose some element of what’s important,” said Chuck Corey, director of the ensemble and keeper of the instruments, “But if you look at it as the whole thing, here was a guy who at a certain point had this vision of working in just intonation, and the direction he decided to go was to build 50 instruments over the course of his life. That’s really interesting.”

I first met Chuck about three years ago after a concert, where he was surrounded, as usual, by the instruments under his care. Dressed in the everyday attire that also serves as the Partch ensemble’s concert dress, he fielded a stream of questions from audience members and performers alike, who wandered freely around the stage: Why is this instrument called the Kithara? Where should we move the Chromelodeon? Can I try out the Cloud Chamber Bowls? At the time I was just an enthusiastic audience member like the rest; there was no way I could have known what kind of impact the instruments would come to have on my musical life.

In a certain sense, Chuck’s story with the instruments began similarly. On his first day of college at Montclair State University, he was introduced to Dean Drummond, the late director of the ensemble who curated the instruments during their stay in New Jersey. After a brief tour of the instruments, one thing lead to another and Chuck quickly found himself playing on concerts, picking up vocal parts, and helping out with instrument maintenance.

“It was exactly what I needed at that point as a composer and student of music: to be introduced to new sounds, new tuning systems, new tone colors,” Chuck said. “Any preconceptions I might have had going into an undergraduate music program were just thrown out on day one.”

After becoming an integral part of both the student and professional ensemble, Chuck moved on to graduate school, but returned after finishing his doctorate. Unfortunately, Drummond passed away soon afterwards, and Chuck found himself as the only person with an intimate knowledge not only of Partch’s often difficult-to-decipher notation systems, but of how to care for the instruments and move them safely from place to place.

“No one else was really fluent in sight-reading the notation, nobody else had gone through the process of what happens when something breaks or how to take the instruments apart and put them back together again,” Chuck said. “So it sort of struck me that either I was going to take this over, or no one was going to do it.”

Somewhere along the way, the Montclair School of Music decided it didn’t have the resources to keep the instruments at the university, and they essentially became homeless. Previous concerts in Seattle had been met with enthusiasm, and faculty at the University of Washington School of Music expressed interest. So after a lot of hard work and a lot of good fortune, Chuck and the instruments made their way to Seattle in 2014, and have been here ever since.

For local percussionist Paul Hansen, good fortune and fate certainly seem to have conspired to bring the instruments here. Amazingly, Paul first heard Partch’s music at the age of 11, thanks to a gift from his father.

“When that first The World of Harry Partch album came out in ’69, [my father] brought it home and said ‘Hey, I think you’d like this.’ Castor and Pollux just put the hook in me, and I said ‘Oh my gosh, I want to play these things someday.’”

Soon, Paul was reading Partch’s explanations of his method in his book Genesis of a Music and listening to any recordings he could get his hands on. Paul’s father had set into motion what would become a lifelong passion for his son, and throughout the years Paul listened to each new recording Partch made while dreaming of someday playing these instruments.

Nowadays, Paul is a fixture of the ensemble by anyone’s standard. With his long gray hair, healthy sense of whimsy, and penchant for the Diamond Marimba, he’s become an indispensable member of the group who seems to embody the quirky spirit of the instruments which we’ve all come to love. During our conversation at a recent instrument move, Paul told me that when the instruments came to Seattle, he was first in line to get on board.

“When they got here I just sort of showed up on the doorstep like a stray dog,” Paul said. “Chuck was just standing there wondering, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’”

One of the beautiful things about the ensemble is that it allows for these sorts of encounters, and that it’s open to anyone in town with a passion like Paul’s. But this hasn’t always been the case: it was only upon moving to Seattle that Chuck decided to open the ensemble up to the community. At Montclair, only current and former students and faculty members could join, effectively keeping the ensemble to a semi-select few.

“You never know what you’re missing by limiting things to just people at the university,” Chuck said. Keeping the ensemble open helps immensely in filling parts for the wide variety of instruments involved in any given piece, and the extra hands are certainly helpful when the instruments need to be packed up and moved to and from the stage. But beyond practical matters, this openness really embodies the spirit of the instruments and the music.

“These instruments really exist to be touched,” Chuck said. “Anytime I do a lecture or a demonstration for a visiting group I try to set aside time at the end for people to get their hands on the instruments, and when people around town ask to get a tour of the instruments I always make sure they get a chance to do that. Sometimes just playing a few strings on the Kithara is enough for someone to say ‘Hey, is the ensemble open to anybody?’”

Other integral members have come to the Partch instruments through the University of Washington, like Luke Fitzpatrick, a local violinist, composer, and the artistic director of the Seattle-based new music collective Inverted Space. Although it was a concert of Partch’s music here in 2012 by Drummond’s New Band Ensemble that really piqued his interest, it wasn’t until the instruments came to UW, where Luke was working toward his doctorate, that he became intimately involved in the ensemble. Luke was immediately interested in exploring Partch’s works for Adapted Viola and voice, and has since started composing his own works for the instrument.

“I have a really close connection to the Adapted Viola since I’ve been playing it so much,” Luke said. “But I think you still connect with all the instruments in certain ways just by playing in the ensemble. It’s a beautiful thing.”

The Partch Ensemble’s resident soprano, Sarah Kolat, also entered the fold through UW. As a scholar of American music, Sarah is passionate about Partch, the unique significance of his work in music history, and especially his writing for voice, which incorporates aspects of speech and plenty of microtones. In fact, Partch’s initial goal in creating the instruments was to be able to harmonize spoken words, which don’t often match the pitches of our usual tuning system. This fixation on the human voice led to what he calls “intoned voice,” a method of singing that Partch felt was more expressive of both the text and the essence of the individual singer.

“If you are an avant-garde or 20th century vocalist,” Sarah said, “and you have the Partch instruments in the basement of the music building, it’s criminal for you to not participate. That was my thinking going into [the ensemble]: in theory, this is something that every 20th century vocalist would want to do, but not many have the opportunity to do it.”

Each of these ensemble members find something different to love in Partch’s music—something which they all say has transformed their musical lives in some way. Luke, for instance, feels a connection to the physicality and movement of Partch’s aesthetic, the way just playing the instruments can turn into a sort of dance.

“It has this philosophy of the performer being connected to the actual performance: your whole body is connected to the playing and the emotion,” Luke said. “Everything is a resonant body, I think that’s the thing that’s so amazing about his music. Obviously you have the instruments, which are resonant bodies, but you also have the actual performers who are also resonant bodies. That’s really changed my outlook on writing and performing.”

Paul, on the other hand, loves the organic nature of the instruments and the music—how amazing it is that these instruments of scavenged materials can make such incredibly expressive sounds. Sarah says this organic sense of personality is something that the audience in Seattle, no matter how much experience they have with classical music, can connect with.

“I think that [Partch’s music] has a much broader appeal than most modern and contemporary music in this town,” she said. “There’s a real warmth and heart in both the ensemble and the music itself. The instruments too: these are a man’s life work. So I think there’s something here that people are really viscerally responding to.”

What all these core members of the ensemble—as well as the dozens of students, faculty, and community members who perform on the instruments—have in common is a deep affection for the instruments and the music. Luke, for instance, referred to each instrument whose box we opened while moving as “a friend of ours.”

While on stage it may look like a large and random assembly of people, the Partch Ensemble in Seattle has really become a community: a group of people who come together to do something rather difficult, rather odd, and rather fun that they all feel passionately about. As Chuck put it, “We’re the ones who care about it, that’s the connection. That’s all you need.”

And that’s why it’s so sad to see them go. Like Montclair University before it, UW has decided not to renew the Partch instruments’ residency here in Seattle, and the collection will likely be moving on to a new home in the coming year. Perhaps it was just a matter of time: like Partch himself, the instruments seem to be inherently nomadic, never quite settling down in one place for long.

For Chuck, the ideal home for the instruments would be somewhere they can be out in a performing hall at all times to be interacted with and played upon. Unfortunately, at least for the moment, it looks like that kind of space is not forthcoming in Seattle. Chuck was clear, though, that departing from Seattle would mean the end of an important chapter in the Partch instruments’ history.

“We have a lot of momentum right now with the ensemble, with the local audience, and with national and international awareness of what we’re doing,” Chuck said. “It would be a shame if we couldn’t continue that.”

It is also worth remembering what we as a musical community in this city will miss with their possible departure. This is something more than another new music ensemble leaving town: it is a loss of the soul, energy, and humor of the Partch instruments, as well as the community they have brought together.

There will at least be a few more chances to see the instruments played in Seattle on Nov. 19, 21, and 22 at UW. The concerts on Nov. 19 and 22 feature works by Partch—including Two Settings from Lewis Carroll and two scenes from The Bewitched—alongside the boundary-bursting music of composers like Henry Cowell and John Cage. The Nov. 21 concert is entirely dedicated to Partch’s music, featuring classics like Barstow, Castor and Pollux, and And on the Seventh Day Petals Fell in Petaluma (one of Partch’s only pieces without voice in which he calls for almost the full range of instruments).

The instruments’ future afterwards, however, is far from certain. Whether you’re a fan of art songs, dance, experimental music, or poetry, the instruments have something for you—something you can’t find anywhere else. And that’s why these last concerts are so special. As we prepare to open a new chapter in the lives of the instruments, my hope is that this November, alongside Partch fans new and old, we can celebrate the instruments’ time here, the friends they’ve made along the way, and the ways in which they’ve changed our city for the better.

The final concerts featuring the Harry Partch Ensemble at UW are Tuesday, Nov. 19, Thursday, Nov. 21, and Friday, Nov. 22, as part of UW’s Festival of Historical Experimental Music for Percussion.

For more information about the Harry Partch Ensemble, please click here.

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –  It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

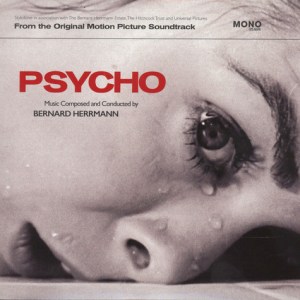

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).