by Michael Schell

Phill Niblock via Festival Mixtur Barcelona.

As a throng of third generation minimalist composers rides the movement’s most fashionable waves, an intrepid handful of the genre’s pioneers continue to sustain it in its original, unalloyed and uncompromising form. Phill Niblock, who turns 85 today, is one of those pioneers. His austere music and sense-saturating intermedia performances are as powerful today as they were at their inception half a century ago.

Niblock’s path to new music was an unusual one. He studied economics at Indiana University, then worked as a photographer and cinematographer for dancers and jazz musicians. His 1966 film of Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra is a classic of its kind. As Niblock became more involved in the New York arts scene, he outfitted his loft in downtown Manhattan as a studio and performance space that soon became one of North America’s most important venues for avant-garde music and intermedia—a distinction it still holds today, over 1000 events later.

Niblock contemplating his creation myth (photo JJ Murphy).

While this was going on, Niblock, following a path established by La Monte Young (the father of drone music and godfather of the more rhythmically active minimalism practiced by Reich and Glass), began to develop his own variety of drone minimalism. A formative experience came while riding a motorcycle up a Carolina grade behind a slow-moving diesel truck:

“Both of our throttles were very open…Soon, the revolutions of our respective engines came to a nearly harmonic coincidence. But not quite. The strong physical presence of the beats resulting from the two engines running at slightly different frequencies put me in such a trance that I nearly rode off the side of the mountain.”

In 1968 Niblock unveiled the result of this epiphany, a style of music built from overlapping layers of sustained instrumental tones, usually multitracked recordings of the same instrument playing closely spaced pitches. There’s no melody, no change of dynamics and no pulse—the close, microtonal intervals create their own beats. What distinguishes his music from that of Young, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros and all the other minimalist composers of his generation, is his consistent emphasis on tight, dissonant harmonies.

Early Winter, from 1993, is a typical specimen. Its 44 minutes feature the Soldier String Quartet, two flutists and 38 channels of recorded sound. It starts on an E♮ drone in octaves, with microtonal neighbor tones entering on either side. These intervals increase to minor and major seconds, and gradually the central drone shifts down to D♮ by the end of the piece. The bright instrumental timbres coupled with the dense texture create clashing high-frequency overtones, and this music is best heard with large loudspeakers powerful enough to fill the listening space.

Even the album covers are minimalist.

The arc of Niblock’s career has been as relentless as this one piece. He has continued to make new work, along the way transitioning from analog tape to digital recording to laptop-based tools. But each new composition is an additional data point along an unbroken line. His oeuvre shows no discontinuities, no sudden breakthroughs, no abrupt shifts in style or aesthetics. Individual pieces differ in their details and their range of timbres, but they all inhabit a shared space that allows them to be chained or even superimposed.

Thus, choosing a favorite Niblock composition often comes down to instrumentation. For sleep time I enjoy the clear tones and natural breath sounds of Winterbloom Too‘s multitracked bass flutes: an enveloping aural blanket without sudden sounds or other distractions. For more intensity, there’s the strident soundscape of Niblock’s Hurdy Gurdy piece. In between is Sweet Potato with Carol Robinson playing a variety of clarinets. Sethwork features an acoustic guitar played with an EBow (a handheld gadget that magnetically stimulates metal-wound strings—it’s normally used with electric guitars). This creates auxiliary buzzes, a cloud of insectoid artifacts that in a Niblockian context seems practically melodic. For hard core listeners, there’s the mammoth Pan Fried 70 (the number is the length in minutes), whose sole sound source is the rubbing of nylon threads attached to piano strings.

The full Niblock effect, though, comes only to those lucky enough to attend a live performance. Most legendary are the annual six-hour winter solstice concerts at his loft that were long a Mecca for the Downtown new music cadre (they still take place, but at Roulette). At their core is an uninterrupted stream of music delivered in loud quadraphonic sound, often enhanced by an ambulatory musician who wanders through the space, doubling pitches from the prerecorded tracks while standing alongside individual audience members.

Accompanying this are several channels of silent video and projected film usually featuring long takes of repetitive human manual labor gathered by Niblock during his travels to dozens of countries all over the world. The movies are minimalistic in their own way, focusing on atomized movement—hands reaching into the frame, the camera moving only to follow the subject—and lacking such traditional cinematic devices as cutaways and reaction shots. In effect, they’re as devoid of gesture as the music is. And just as the music’s rhythm is mainly limited to the natural acoustic interactions of the multitracked sounds, the cinematic rhythms are likewise limited to the intrinsic motion in the shots themselves. You can see an excerpt from Niblock’s film China combined with Early Winter above, and a glimpse of a typical live Niblock intermedia presentation can be seen in this performance preview from the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

With Joan La Barbara in 1975.

As a concert producer, Niblock has had a personal impact on literally hundreds of musicians. As a composer, his influence is prominent in the music of his contemporary Éliane Radigue, several members of the next generation (including Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham and Lois V. Vierk), and a multitude of still younger musicians raised on newer digital tools that facilitate the creation of static, multilayered music. Recent examples of the latter include Lea Bertucci’s Sustain and Dissolve (with its multitracked detuned saxophone drones) and Jordan Nobles’ Deep Breath (for multitracked, slowed down flutes).

Today’s conference centers and dance clubs love to tout their “immersive” facilities, equipped with splashy video walls aiming high-tech wallpaper at the attending retinas to the 360° accompaniment of beat-driven consonance. The intent of this encirclement is, ironically, to drive everyone’s attention in the same direction. Meanwhile, in a far less pretentious building on New York’s Centre Street, there remains at least one steadfast practitioner of an art that is likewise immersive but sincere, fueled by an admiration for the complexity of raw sound and a respect for the cycles of shared human experience. Niblock’s art manages to be of our time, but not of our clichés. It invites each of us to foster a personal relationship with its materials, whether abstract or mundane. It proves that you don’t have to be dazzling to be astounding.

Niblock at his loft with Shelley Hirsch (seated) and Katherine Liberovskaya (photo from the Wall Street Journal).

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –

As an avid hiker, I couldn’t resist Vincent Raikhel’s Cirques. A reflection of the glacial geological formations so often encountered in the Cascade Mountains, this piece immediately transported me to a faraway corner of the imposing mountain range in Seattle’s backyard. In the context of the Spooky Music Marathon, this piece made me think of the creeping claustrophobia that one might feel in a cirque, especially as the sun sets, as it does so quickly in the mountains. It’s curious, how something so open to the sky, so large and static, can suddenly feel as if it is closing in on you in the waning light… –  It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

It just wouldn’t be a Halloween marathon without a spooky clown—and Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire is nothing if not haunting. A masterpiece of melodrama, the 35-minute work tells the chilling tale of a moonstruck clown and his descent into madness (a powerful metaphor for the modern alienated artist). The spooky story comes alive through three groups of seven poems (a result of Schoenberg’s peculiar obsession with numerology), each one recited using Sprechstimme: an expressionist vocal technique that hovers eerily between song and speech. Combine this with Schoenberg’s free atonality and macabre storytelling, and it’s enough to transport you to into an intoxicating moonlight. –

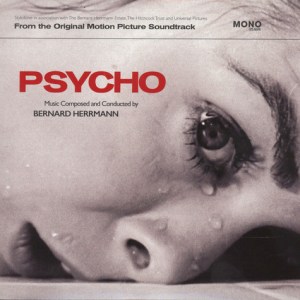

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).

This piece is so timelessly cool and undeniably scary. Like John Williams’ Star Wars score borrowed the dark side of the Force from the dojo-dominating “Mars, the Bringer of War” in Holst’s The Planets, Herrmann borrows the creepy suspenseful stringiness of Norman Bates from the dancing skeletons in Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (and maybe from Mussorgsky’s Bald Mountain witches).