The cover of Into the Anthropocene, Grammy-nominated composer Pascal Le Boeuf’s new video EP, is a photo from the Trinity nuclear test of 1945. That’s because the Manhattan project’s successful test of the atomic bomb is widely considered to be the start of the Anthropocene epoch, an ecological era characterized by significant changes in the earth’s ecology and biodiversity as a result of human activity.

The cover of Into the Anthropocene, Grammy-nominated composer Pascal Le Boeuf’s new video EP, is a photo from the Trinity nuclear test of 1945. That’s because the Manhattan project’s successful test of the atomic bomb is widely considered to be the start of the Anthropocene epoch, an ecological era characterized by significant changes in the earth’s ecology and biodiversity as a result of human activity.

Into the Anthropocene tells the story of humanity’s impact on the earth in three movements: “Cognitive Awakening”, “Requiem for the Extinct”, and “Amid the Apocalypse.” With the use of electronic layering, “Cognitive Awakening” features Gina Izzo on the flute, bass flute, and piccolo—sometimes all at once.

As a somber, legato melody unfolds over long, sustained chords, the piece is augmented by birdlike twittering from the piccolo, key clattering, electronic sounds, and muffled dialogue that can’t quite be made out. “Cognitive Awakening” is a beautiful evocation of nature, but at the same time, a sobering reminder of what has been lost—and what might still be lost.

We’re thrilled to premiere the video for Le Boeuf’s “Cognitive Awakening,” performed by Gina Izzo.

Learn more about Le Boeuf’s new piece in our interview with the composer below:

Second Inversion: Into the Anthropocene features three movements scored for the flute family, viola, and cello, respectively. What was the inspiration behind this form and how do the individual movements relate to one another?

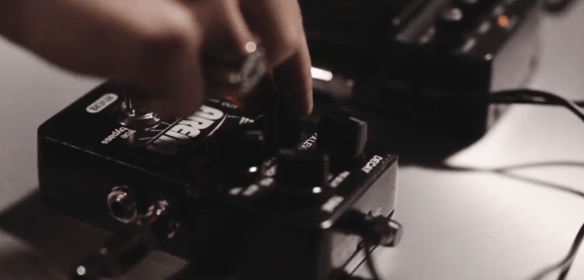

Pascal Le Boeuf: Into the Anthropocene is scored like a lead sheet to be inclusive of any instrument. The score specifies only the most essential elements to dictate structure, basic ideas, and guide improvisation. Beyond the conservation ecology concept, my intention was to create a series of simple pieces to invite classically trained musicians to experiment with improvisation and hardware electronics (guitar pedals). I generally engage with improvisation as a compositional device to provide performers with a platform for self-expression. This allows for a different interpretation with each performance (as opposed to a ridged set of directions to translate the composer’s singular intended expression).

Pascal Le Boeuf: Into the Anthropocene is scored like a lead sheet to be inclusive of any instrument. The score specifies only the most essential elements to dictate structure, basic ideas, and guide improvisation. Beyond the conservation ecology concept, my intention was to create a series of simple pieces to invite classically trained musicians to experiment with improvisation and hardware electronics (guitar pedals). I generally engage with improvisation as a compositional device to provide performers with a platform for self-expression. This allows for a different interpretation with each performance (as opposed to a ridged set of directions to translate the composer’s singular intended expression).

Commissioned by choreographer Kristin Draucker for the Periapsis Open Series, Into the Anthropocene was written for violinist Todd Reynolds whom I met at the Bang on a Can Summer Music Festival in 2015. I worked with Todd as well as violinist Maya Bennardo while at Bang on a Can, and later completed the piece with the help of violinist Sabina Torosjan while in residence at the I-Park Foundation’s 2015 Composers + Musicians Collaborative Residency Program. In addition to performing with electronics and improvising in his own music, Todd occasionally works as an educator, specializing in improvisation and electronic music. He has always been kind to me, offering advice and artistic input, especially when I was first began working with “contemporary classical” identifying musicians. I wanted to return his kindness with a piece of music, so when choreographer Kristin Draucker commissioned me to compose a piece, I thought of Todd immediately.

Unfortunately, due to unforeseen circumstances, Todd was suddenly unable to attend the recording session, so the same day, Todd and I called the best musicians we knew who were uniquely qualified to perform the music (i.e. musicians with experience in classical, improvisation, and electronic music). I thought it best to split the responsibility between multiple performers, and assigned the movements based upon the musical personalities of the performers: Mvt 1 – flutist Gina Izzo, Mvt 2 – violist Jessica Meyer, and Mvt 3 – cellist Dave Eggar. In retrospect, I see this outcome as a happy accident, which not only benefited the music by introducing a variety of timbres and musical personalities, but led to numerous collaborative projects with these wonderful musicians.

The formal structure of the three movements, and the conservation ecology concept in general, were initially inspired by author Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind and were further developed through conversations with notable conservation biologist Claudio Campagna and ecological/behavioral biologist Bernard Le Boeuf (my father).

In Sapiens, Harari recounts our history as a species through a lens of evolutionary biology, postulating that biology sets the limits for global human activities, and that culture shapes what happens within those limits. I became particularly interested in prehistoric sapiens, their initial diaspora, the cognitive revolution, and the resulting extinctions of other species as a result of human impact. Following the cognitive revolution, humans developed the skills necessary to expand beyond the Afro-Asian landmass into Australia, the Americas, and various remote islands. Before humans intervened, these hosted an array of unique and flourishing species ranging from two-and-a-half ton wombats in Australia, to giant ground sloths and saber-toothed cats in the Americas. But without exception, within a few thousand years of setting foot on these territories, humans managed to kill off tremendous collections of diverse species. As Harari puts it, “Homo sapiens drove to extinction about half of the planet’s large mammals long before humans invented the wheel, writing, or iron tools,” including other human species with whom we once coexisted and even interbred.

As a musician, I find it interesting to explore the extensions of patterns in sound, but when we consider the extensions of the destructive behavioral patterns we exhibit as a species, it is difficult to imagine a positive outcome. The three sub-movements (I: Cognitive Awakening / II: Requiem for the Extinct / III: Amid the Apocalypse) outline the past, present, and future of our ecological history. Through Harari’s lens, conversations with Campagna and my father, and subsequent research, I learned about the extent to which our planet is currently experiencing a crisis of mass extinction. We are losing species, whole ecosystems, and genes at an ever-increasingly rapid rate. Today, species disappear each year at a rate hundreds of times faster than when humans arrived on the scene. As a species known for 100,000 years to bury our dead, it is amazing we have such little respect for the deaths of other species, dozens of which are disappearing daily as a result of human activities—activities sufficient to mark a new epoch based upon human impact on the Earth’s geology and ecosystems: the Anthropocene.

SI: How does “Cognitive Awakening” relate to the beginning of the Anthropocene and human impact on the Earth?

PLB: The cognitive revolution is a precursor to our dominance as a species and thus a precursor to the Anthropocene. According to Harari, humans became a dominant species through our ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers—an ability derived from our unique capacity to believe in things existing purely in the imagination. The evolution of this ability is referred to as the Cognitive Revolution (c. 70,000 BCE). The first movement represents this cognitive awakening musically through an additive progression of increasingly complex elements. Something like this:

- Static noise

- Static droning

- Melody

- Harmony

- Call and Response

- Speech

- Improvisation

- Electronic Manipulation

I like to imagine that the evolutionary progression that resulted in language, expression, and cognitive awareness has an analog in the development of music. This is how I chose to represent such a progression based upon my personal understanding of music (and perhaps based on the order in which many learn/teach music).

SI: Into the Anthropocene features a lot of electronic layering and manipulating sounds. How does this compositional choice tie in with the overarching themes of the piece? What were some of the unique challenges or rewards of composing in this way?

My intention was to create a series of simple pieces to invite classically trained musicians to experiment with improvisation and hardware electronics (in this case, guitar pedals). Though I have a background in electronic music and enjoy complex approaches, I made a special effort to keep the electronic elements simple and accessible to performers without prior experience in electronic music.

Guitar pedals can be acquired easily at various prices at nearly any music store and are much easier to use than complex software programs like Max MSP, Protools, Logic, etc. (and are easier to understand). Each pedal represents a sound effect (in order from input to output): loop, reverb, vibrato, and delay. Each sound effect has basic parameters that are uniform across most brands. I hope that more classically trained musicians will be encouraged by this project to experiment in a similar fashion, as a gateway into composition, independent artistic development, and interdisciplinary collaborations with artists from backgrounds that transcend traditional classical environments. Every musician involved in this project is a wonderful role model for unconventional approaches to a career that began in classical music.**

**(Dave Eggar, a founding member of the FLUX Quartet, can also be heard on the opening of Coldplay’s Viva La Vida or Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange; Gina Izzo frequently performs with pedals in various contexts, and co-founded the flute and piano duo RighteousGIRLS; and Jessica Meyer, in addition to performing a one-woman show with loop pedal and viola, is a fantastic composer with recent premieres by A Far Cry, PUBLIQuartet, and Roomful of Teeth.)

The compositional choice to include electronic elements preceded the conceptual development of the piece. I view these electronic elements as raw materials for expression, and worked with them to articulate the conservation ecology concepts I described earlier. Most of the compositional challenges I faced were related to the strict parameters imposed by the loop pedal. Using a basic loop pedal means the form of each movement is additive, and will inevitably look something like this:

1

1+2

1+2+3

1+2+3+4

1+2+3+4+5

…with elements of improvisation and knob turning interspersed between stages.

More complex loop pedals offer more structural options, but I wanted to keep this simple. Fortunately, placing the loop pedal at the beginning of the signal path allowed the subsequent effects pedals to sculpt/develop the existing looped material. Additional challenges included working with each performer to translate the score for their instrument. Since the composition doesn’t specify a particular instrument, I had the pleasure of working with each performer to find extended techniques that produced the desired effects. For example, Dave imitates a rhythmic shaker at the beginning of Mvt III by swiping his hand back and forth along the body of his cello, but if Gina were to imitate a shaker, she would blast air into her mouth piece with consonant sounds like this: [T k t k, T k t k].

The most rewarding aspect of this process is seeing how different performers interpret the music, and how rewarding the process of interpretation can be. Frequently, especially when performing standards, jazz musicians will prioritize the creative expressions of the performer over the composer. One might say the composition is not what makes the music work, but the way it’s played. When John Coltrane plays “My Favorite Things,” it sounds good because of the way he and the band play it—it’s not about the composition. The composition it just a guide. This freedom allows performers a chance to put themselves in the music, self-expression, a cathartic release. Audiences can feel it when it’s happening. I want to bring this aesthetic to classically-trained musicians. These movements are only a guide to highlight the individuals performing them. The performers and what they think about when they interpret this music… they make it work. I only provide a platform.

Pascal Le Boeuf’s Into the Anthropocene video EP will be released April 20. The album art photo is from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and was taken 16 milliseconds after the first atomic bomb test.

Click here to pre-order the video EP on Bandcamp.

At the same time, though, this coupling highlights a prejudice that continues to haunt conventional narratives of Western art music. Of these two musicians—both of similar age and similar stature among musicians, and both clearly capable of articulating a shared musical language in a public space—only Oliveros is consistently mentioned in textbooks and retrospectives on contemporary classical music (see, for example, the otherwise admirable surveys by

At the same time, though, this coupling highlights a prejudice that continues to haunt conventional narratives of Western art music. Of these two musicians—both of similar age and similar stature among musicians, and both clearly capable of articulating a shared musical language in a public space—only Oliveros is consistently mentioned in textbooks and retrospectives on contemporary classical music (see, for example, the otherwise admirable surveys by