In the fledgling years of electronic music—the 1950s and 60s—European composers benefitted from the massive support offered by government-owned broadcast studios. Varèse, Stockhausen and Berio created their midcentury masterworks at radio stations equipped with multiple tape recorders and vintage oscillators and filters. American pioneers like John Cage and Pauline Oliveros had to scrape by with homemade instruments and the more modest furnishings of university studios and artist collectives. And their recordings were often drowned out in LP catalogs by their state-sponsored European counterparts.

It was in this environment that Nonesuch Records stepped up, offering the label as a platform for electroacoustic compositions by Cage, Dodge, Wuorinen and Gaburo, as well as Morton Subotnick’s Silver Apples of the Moon (1967), the first tape piece ever commissioned by a record company. Another work commissioned by Nonesuch was an album-length epic called Tragoedia, released in 1969 and created by Andrew Rudin, a Texan who taught for several decades at University of the Arts in Philadelphia and who today is celebrating his 80th birthday.

Switched-On Mahler

Tragoedia was made with an early Moog synthesizer of the sort popularized by Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach. It had a grittier sound then the Buchla synthesizers heard in Subotnick’s music, and its controls made it more suitable for complex, gradually-changing sonorities than the beat-driven patterns facilitated by the Buchla’s sequencer-centric design. Tragoedia‘s sound palette is purely electronic—there are no concrète (prerecorded) sound sources in the piece.

Rudin (who pronounces his name roo-DEEN) conceived Tragoedia as an exploration of Greek tragedy. But with its familiar four-movement structure, I hear it as more of a synthesized symphony, a modern microtonal organism built from rhythm and timbre but supported by a traditional skeleton.

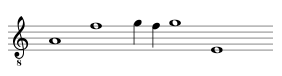

Viewed this way, the first movement, Kouros, stands in for a sonata-allegro. It begins with a three-chime “alarm clock” that launches a long sinuous paragraph filled with sliding sawtooth waves that culminate abruptly at 1:29 with four “bass drum” stokes. This passage is repeated with some variations, whereupon at 3:29 we hear a new idea, comparable to a sonata form’s second theme, based on short notes that sound like dripping water. At 4:16 an oscillator plays the first real melody of the piece before it too is cut off by bass drum strokes:

The foregoing ideas are now combined and recombined in the manner of a classic development section. The alarm clock gets its solo moment starting at 7:00, and at 8:10 the quoted melody returns a half-step higher. The bass drum tries repeatedly to shut it down, finally succeeding after one last loud stroke.

The second movement, Hybris (“hubris” in modern English), functions as a scherzo. In place of the opening movement’s long contrapuntal lines, Hybris is mainly a succession of brief motives spliced together in a kind of monophony. Headphones will help you hear the fancy stereo effects (e.g. at 1:25). The coda is remarkable: a rising accelerando (created by tape playback with increasing speed) that ends with a dramatic tocsin.

Peitho features fast flurries of randomly-generated tones in counterpoint with slowly shifting sustained sounds. It’s a kind of intermezzo setting up the long final movement, Até, which resembles one of those resigned adagios that often come at the end of Mahler symphonies. A high gated sound that resembles an impulse sprinkler recurs throughout Até as a refrain, usually panning from one ear to the other. The melody from Kouros returns, along with other ideas from the previous movements. The coda features an extended two-voice canon that eventually subsides, leaving the last fleeting words to the impulse sprinkler.

Though Tragoedia’s neoclassicism is not as groundbreaking as the montage structure of Varèse’s Poème électronique or the process-driven form of a minimalist landmark like Come Out, its sound world—still fresh and novel in 1969—impressed Federico Fellini enough to incorporate excerpts from it (without the composer’s permission) in the soundtrack to his Satyricon.

In and out of style

As the 1980s ushered in the age of CDs, major disruptions came to the recording industry. Nonesuch was brought under tighter control by its corporate masters at Warner, and the venerable electronic music titles started to drop out of its catalog. Simultaneously, modular synthesizers gave way to digital instruments, and as Gen Xers fawned over the new MIDI synths with their unprecedented portability and programmability, they gradually lost interest in the monuments and artifacts of the old ways.

But things can change over the course of a generation. The emergence of streaming and downloadable media in the 21st century made it easy to reclaim old recordings for digital distribution. And millennials grew tired of the canned timbres produced by their parents’ Korgs and Yamahas. Eager to reintroduce some irregularity into their sound world, they returned to analog technology, now much improved over its first generation, and this in turn rekindled interest in early synthesizer music. Now Tragoedia and its breathren are back, readily accessible online through Spotify, Amazon and YouTube. So grab your headphones, dim your room lights, and (re)connect with this nugget from the golden era of electronic music.