This post is part of a series on John Cage’s “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse).” For earlier installments of the series, please visit: Introduction & Part I

“There’s a temptation to do nothing simply because there’s so much to do that one doesn’t know where to begin,” John Cage whispers into my ear blandly. “Begin anywhere.”

After nearly 30 minutes of staring off into space wondering how in the world to process Part II of his massive, eight-part sound art masterpiece “Diary,” I figured that was pretty sound advice. After all, each section of John Cage’s “Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)” begins anywhere, ends anywhere, and travels to any number of places in between.

“We’re getting rid of the habit we had of explaining everything,” he says—which I suppose explains why the entire “Diary” is so fragmented. Cage drastically changes topic nearly every sentence, leaving the listener (and in this case, the reader) to create their own contexts and connections within or between the jumbled phrases.

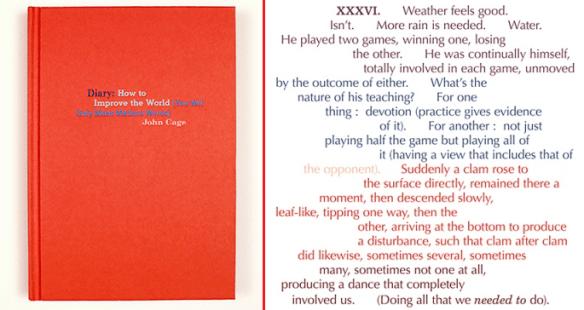

And trust me, the jumbled phrases truly span the gamut: from politics to philosophy, environmentalism to electronics. His writings discuss music, art, love, war, chess, and surprisingly frequently, mushrooms. (Cage was, in fact, an avid amateur mycologist and took great interest in the study of fungi). But what interested me most as I flipped through the bold, red-orange edition published last month by Siglio Press, were Cage’s musings on the state of contemporary art.

“To know whether or not art is contemporary, we no longer use aesthetic criteria (if it’s destroyed by shadows, spoiled by ambient sounds); (assuming these) we use social criteria: can include action on the part of others,” Cage says in his typical matter-of-fact manner. “We’ll take the mad ones with us, and we know where we’re going. Even now, he told me, they sit at the crossroads in African villages regenerating society. Mental hospitals: localization of a resource we’ve yet to exploit.”

While Cage is certainly not the first composer to take an interest in the social criteria of music (Ives was influenced by American popular and church music traditions, Bartók was inspired by Eastern European folk music, and so on), he’s certainly among the first to give so much creative control to his performers and to his audience. As for the mental hospitals: madness is really just unpredictability—and for Cage, so is music. Chance operations and indeterminacy allowed his pieces to be living, breathing works.

“My favorite music is the music I haven’t yet heard,” Cage wrote in his 1990 autobiographical statement. “I don’t hear the music I write. I write in order to hear the music I haven’t yet heard.”

Which would perhaps explain Cage’s keen interest in percussion. After all, percussion is really just the sounds you hear between stretches of silence—whether you are in the concert hall, on the street, in the countryside, or by the sea. Percussion is the simplest, most primordial, and likewise most universal music.

“I remember clams from the Sound exhibited years ago in a Seattle aquarium (near the Farmer’s Market, admission ten cents): their movement, their timing of it,” Cage recalls in his diary. “They were a bed, immobile, one on top of the other, two feet deep in a tank of water, sand on the bottom of the tank. We were told to wait.”

In other words: silence.

Cage all but changes the subject entirely before returning to this anecdote later on in his diary entry. He talks about the weather, the rain, education, devotion, and a game of chess before he meanders back to his Seattle aquarium story:

“Suddenly a clam rose to the surface directly, remained there a moment, then descended slowly, leaf-like, tipping one way, then the other, arriving at the bottom to produce a disturbance, such that clam after clam did likewise, sometimes several, sometimes many, sometimes not one at all, producing a dance that completely involved us.”

Cage does not describe the actual sound of this dance, but he is clearly describing the music of it. The sporadic rhythm of movement, the dancing, the descent—what else could it be? Perhaps the anecdote is meant to illustrate the universality of music, its existence all around us, and the ways in which we might experience music without necessarily hearing it.

After all, it was in 1952 that Cage created the first “happening”: a bold and unusual performance art event that took audiences out of the concert hall and into, well, the outside world. Like many of Cage’s works, his happenings are difficult to describe; by nature each is a completely unique performance event occurring in the present, enabling the audience to forget the past and future and instead become fully immersed in the music of the present—the music of the world around them.

Much of the specifics of these happenings were left entirely up to chance. Depending on the piece, the actual orchestration of his happenings range from television sets to toy pianos, “any number of people performing any actions” to no music or recordings at all. In fact, several of these wide-ranging happenings were part of an eight-part series he cheekily titled “Variations.”

As for duration of the happenings, that was typically left up to chance, too. Although according to Cage’s philosophy, the music continues infinitely all around us, even once the specific piece has ended.

“(Music’s made it perfectly clear: we have all the time in the world,” he says dryly. “What used timidly to take eight minutes to play we now extend to an hour. People thinking we’re not occupied converse with us while we’re performing.)”

Go to the next installment: Diary: How to Read John Cage – Part III

Pingback: Diary: How to Read John Cage – Part VII | SECOND INVERSION

Pingback: Diary: How to Read John Cage | SECOND INVERSION